Schools Are Using NIL Buyouts Instead of Noncompetes to Deter Athletes' Movement

Courts should be skeptical of the trend

College sports keeps reinventing the same labor-constraining contract devices and pretending they’re new.

The latest example comes from Georgia, where the university is suing Damon Wilson, a former Georgia football player who now plays (works) for Missouri. Georgia seeks roughly $390,000—the unpaid balance of a NIL agreement Wilson signed last year. As ESPN summarizes the arrangement:

Wilson signed a term sheet with Classic City Collective in December 2024, shortly before Georgia lost in a quarterfinal playoff game to Notre Dame, ending his sophomore season. The 14-month contract -- which was attached to Georgia’s legal filing -- was worth $500,000 to be distributed in monthly payments of $30,000 with two additional $40,000 bonus payments that would be paid shortly after the NCAA transfer portal windows closed.

The deal states that if Wilson withdrew from the Georgia team or entered the transfer portal, he would owe the collective a lump-sum payment equal to the rest of the money he’d have received had he stayed for the length of the contract. (The two bonus payments apparently were not included in the damages calculation.) Classic City signed over the rights to those damages to Georgia’s athletic department July 1 when many schools took over player payments from their collectives.

Georgia’s filing claims Wilson received his first $30,000 payment Dec. 24, 2024. Less than two weeks later, he declared his plans to transfer.

The case matters because NIL “buyouts” could easily become the default legal technology for restricting athlete mobility. This would functionally replace noncompetes in a domain where noncompetes are both politically and legally radioactive.

This post looks at the enforceability of liquidated-damages provisions in NIL agreements. More broadly, it fits in my ongoing interest in how firms keep trying to dodge public-policy limits through contract design.

Back to Wilson’s case, which is currently before a Georgia court on a motion to compel arbitration. In the underlying Term Sheet,1 Damon assigned rights to use his NIL to the Association, which got the right to declare that assignment terminated if Damon left Georgia.

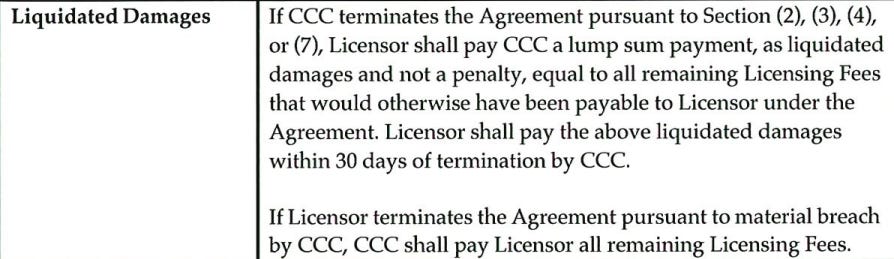

If the Association exercised that termination option, the Term Sheet required Wilson to pay “Liquidated Damages.”

Three features of this arrangement are especially striking.

First, the idea that enforceable liquidated damages can simply match what the university would have paid the athlete is doctrinally fraught. Of course, there’s tons of precedent upholding the use of such provisions in place of noncompetes for coaches in college sports. But usually that’s because at the heart of the case there’s a well-compensated individual whose departure will cause the college definite but hard-to-calculate harm.

In Young Harris College v. Peach Belt Athletic Conference (Ga. Ct. App. 2025),—a case about a college’s exit, not a person— the court applied a familiar test: “First, the injury must be difficult to estimate accurately. Second, the parties must intend to provide damages instead of a penalty. Finally, the sum must be a reasonable estimate of the probable loss.”

Here, unlike cases where unpaid coaching salaries proxy for recruiting disruption and institutional harm, it is hard to argue that the value of a single athlete’s NIL rights is fairly measured by the salary he would have received for continuing to play.

Sure, the collective can claim “brand value” loss or reduced ROI on marketing. But the harms are small, speculative, individualized, and easily measured ex post (that is, they can get a measure of sales!) This is not a conference losing a founding member or a university losing a $5M-a-year coach. It is an endorsement contract. If the athlete only completed 20% of the contracted appearances, the damages math doesn’t easily satisfy the first or third parts of the test. And it plainly fails the test’s second intent prong as well. The point of the clause is not compensation but deterrence: to make mid-agreement transfer prohibitively expensive. The language in the agreement on this point “and not a penalty” is notably perfunctory, and I’d guess that discovery would reveal even more juicy quotes.

Indeed, the liquidated-damages trigger reveals the real aim of the agreement. Only one kind of conduct matters: leaving Georgia. There are 16 default events listed in the agreement. The LD clause is triggered by failing to enroll at UGA, withdrawing from the team, and breaching obligations related to future NIL agreements. Not included? Being charged with or being found guilty of a crime or engaging in acts of moral turpitude, violating team rules, misrepresenting facts about his background that would affect the value of the license, and dying. That is, the only thing that triggers the repayment obligation (more or less) is not playing for Georgia. An athlete could obliterate his brand value—even through criminal conduct—and the collective would still have to prove actual losses.

Third, the irony is that a university asserting heavy-handed control over athlete mobility chose a thin, underlawyered “Term Sheet” that raises threshold enforceability questions. There’s no choice of law clause. The arbitration clause is vestigial. It’s a Term Sheet, with a to-be-formalized version of a contract missing. You’d think that if the University wanted to throw its weight around, it would find a player who had finished the process of executing a real contract, so that, at a minimum, the governing law would be clear.

In all events, that’s just my drive-by thoughts about this particular case, which of course could change with the facts.

The more interesting question is why schools and collectives are using damages to restrict athlete mobility at all. The answer is obvious: they are trying to recreate the coaching buyout model in miniature.

Head coaches jump around constantly, so schools write contracts that price exit rather than prohibit it. Vanderbilt v. DiNardo (1999) is canonical.2 The Sixth Circuit blessed a clause that required the departing coach to pay Vanderbilt an amount keyed to remaining salary—a straightforward liquidated-damages structure. And it did so over DiNardo’s argument that this was merely a disguised (and prohibited) noncompete.

In the years since DiNardo, the trend in the South has been pro-noncompete (somewhat counter to the national movement). But coaches—who have gained in power—clearly prefer the LD equilibrium since they can get the new employer to buy out the old. Thus, even though schools in the SEC could probably move toward noncompetes, they won’t, because they are chasing talent.

NIL collectives have copied the script. But they are doing so without the same substantive bases for enforcing the LD clause, and (as I’ve discussed) are creating additional legal vulnerabilities. And given how quickly college athletes’ marketable skills erode, noncompetes would create really powerful leverage and could buttress team cohesion. So, why haven’t schools used these devices to protect their NIL payments?

I think it’s a mix of the following:

Antitrust: After Alston and the capitalized damages suits, nobody is eager to defend an explicit “you may not play elsewhere” covenant. By contrast, antitrust still looms over liquidated damages, but only indirectly. A buyout is framed as pricing breach, not suppressing competition. Courts often accept that framing at face value.

The employment status trap: The more an NIL contract looks like an employment restriction—complete with a noncompete—the easier it becomes for athletes to argue they are employees. Collectives and schools do not want that fight. Again, LD are slightly easy to characterize as not about employment (though the details matter).

Politics and optics: Even in pro sports, noncompetes are rare. Fans accept buyouts. Fans probably would not accept formal restraints on a player’s right to work. A collective that tried to impose a genuine noncompete on an athlete would become the villain in the story.

So we get LD clauses instead. Not because they’re doctrinally safer in the abstract, but because they’re rhetorically easier to sell and incrementally less exposed to antitrust scrutiny.

Ok. So, what should happen in general? In my view, liquidated-damages clauses in NIL agreements should be presumptively suspect. Courts should (and maybe will) require real ex ante harm estimation to bless them. And they should treat disproportionate buyouts as functional restraints on mobility — penalty clauses — and not damage estimates. That approach would align liquidated-damages doctrine with antitrust principles and prevent schools from arbitraging their way around Alston.

The operative agreement is apparently the “Term Sheet,” which contains within the puzzling provision that “In the event the parties agree to this Term Sheet, then they shall work cooperatively to set forth these terms in a full legal contract including all the standard provisions of NIL licensing agreements.” No where in the arbitration demand is any subsequent contract mentioned. I suppose one issue in any subsequent litigation will be whether this document can create enforceable obligations.

It’s wild how many cases I think of are canonical are ones that happen to be in my contracts casebook.