Consumer Contracts are Fairly Readable, Suprisingly Sloppy, and Sometimes Irrelevant

Recent papers that changed the way I thought about contract law

Half of American adults can’t read at an 8th-grade level. Or so you’ve heard.

Turns out, that’s a myth—though one that’s shaped legal reform efforts for decades.

In this edition of Contract’s Empire, I’ll look at three recent papers that challenge popular beliefs about consumer and employment contracts: that they’re unreadable, that they’re purposefully exploitative, and that they reflect the cold logic of market Darwinism.

It turns out that none of this is exactly true. Consumer contracts are often sloppy, weird, and—surprisingly—readable.

Paper #1: “Readability” Scores Are Mostly Junk

Yonathan Arbel, The Readability of Contracts: Big Data Analysis, 21 J. Emp. Stud. 927 (2024).

Late last year, Alabama’s Yonathan Arbel published an important empirical paper on contract readability that you should read.1 It left me with three lasting takeaways.

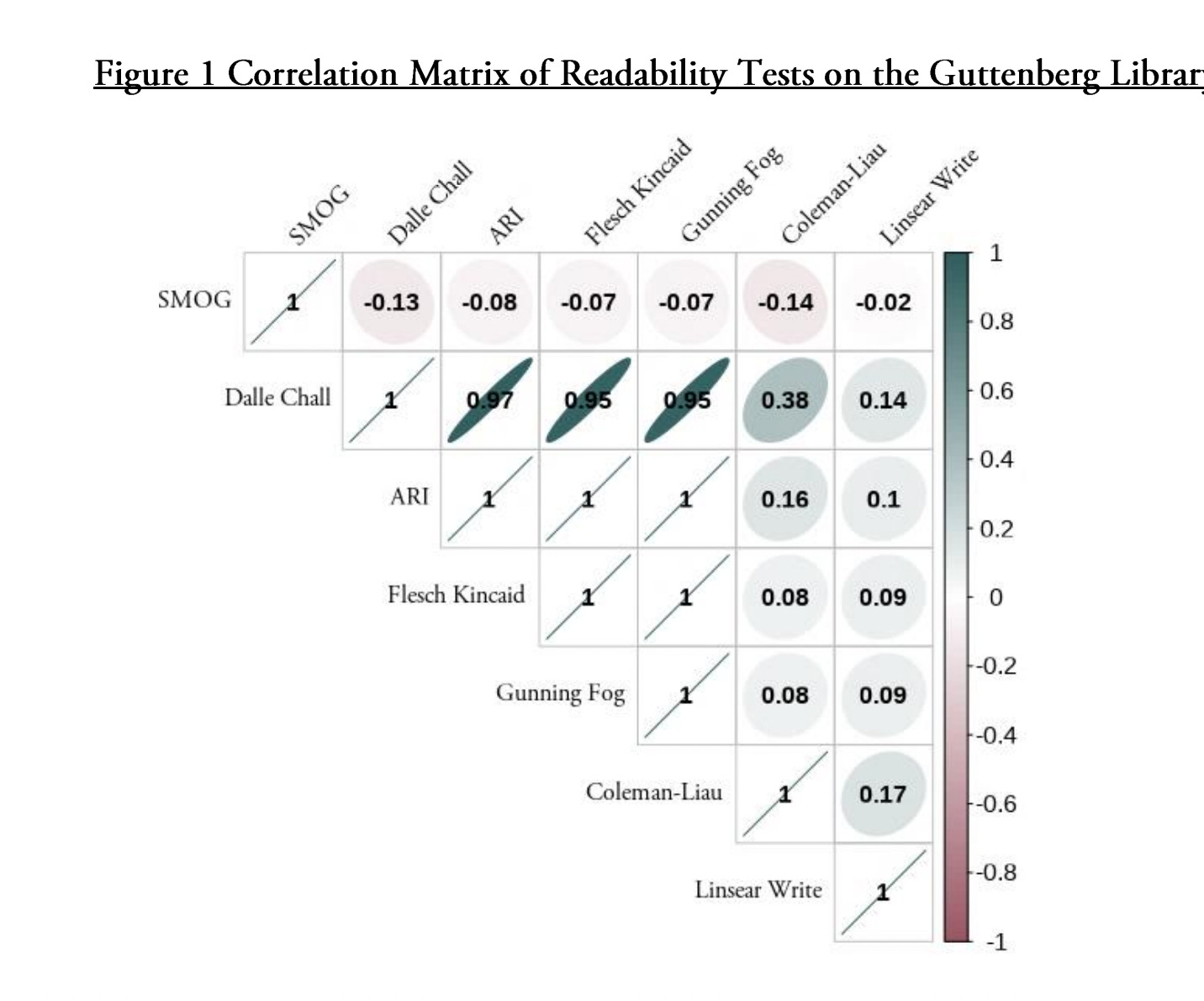

Arbel puts together a mountain of evidence that readability scores are incoherent, internally and externally unreliable: you shouldn’t use them. As he shows (using a ginormous corpus of books) the various tests don’t even correlate well to each other!

The upshot: “readability” is a surprisingly hard concept to quantify, and our existing measures are so bad that we should be skeptical of any legal reform proposals based on them. That includes the Plain Language Movement for contract and statutory law. But it also should update your priors when you hear that a particular contract or document is “too hard” to read. By what measure?

You’ve heard that half of American adults can’t read at an 8th grade level, right? Well, Arbel tracked down the source of this factoid and has found it about as well sourced as the myth that 60 percent of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck. And the evidence to the contrary is overwhelming.

Apart from enabling you to be a contrarian at dinner parties, why should you care? For me, the takeaway is how often this particular idea—that lay people are functionally illiterate—comes up in judicial decisions and legal scholarship. And evidence of how much low-hanging fruit there is in the empirical study of law.

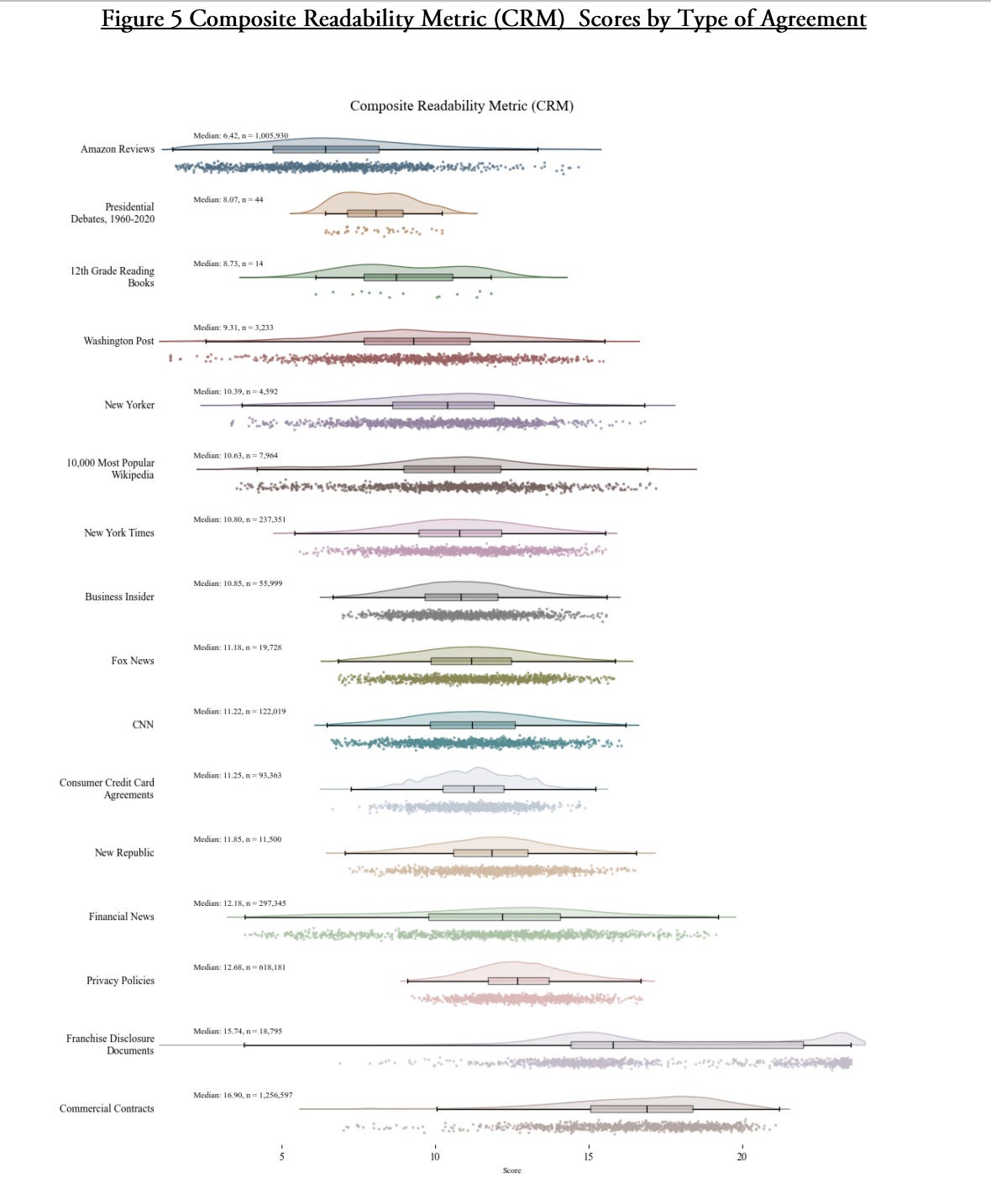

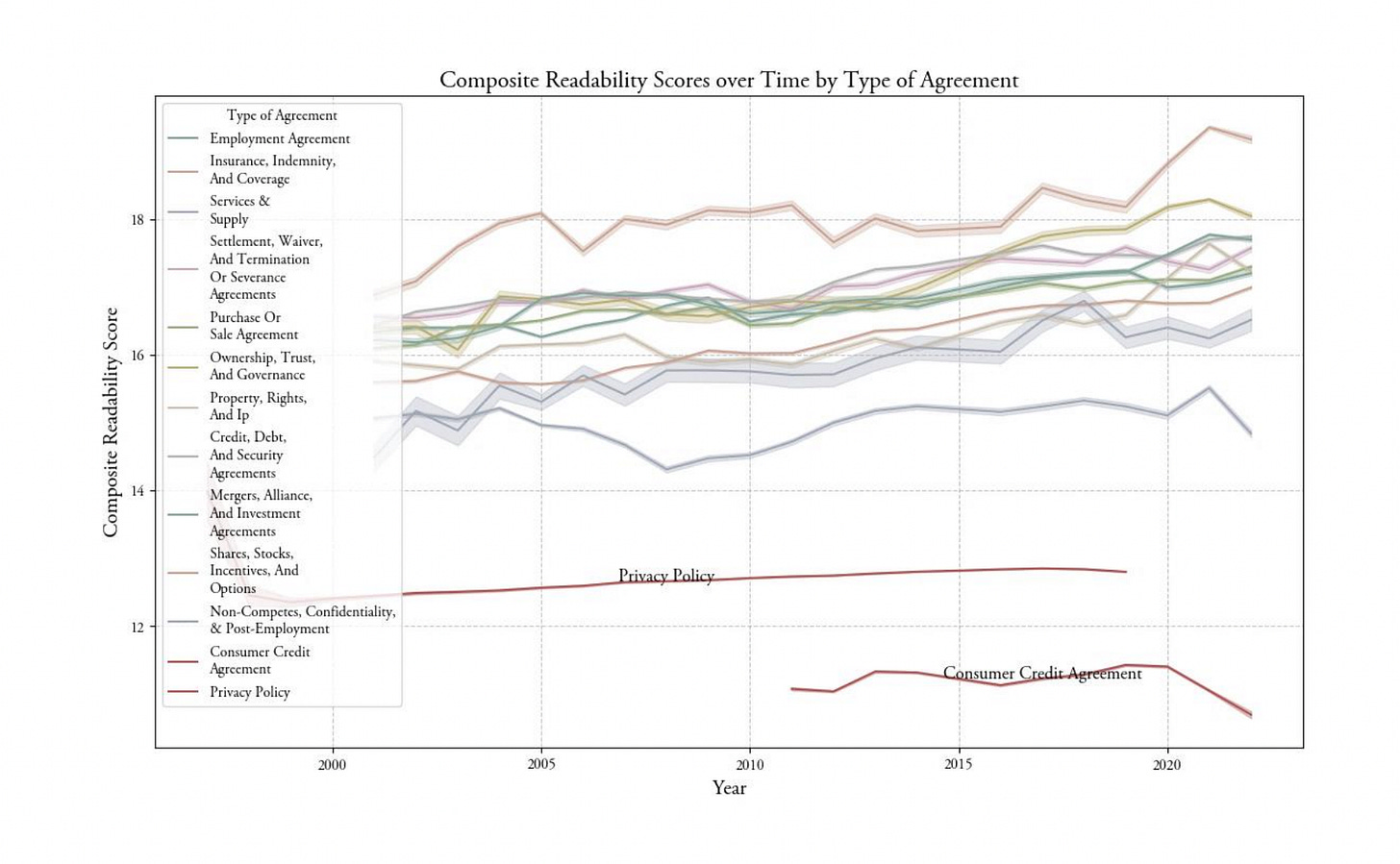

Finally Arbel uses machine learning techniques to parse and then compare the readability (measured as a composite of all existing measures) of a variety of kinds of text (which he collected).

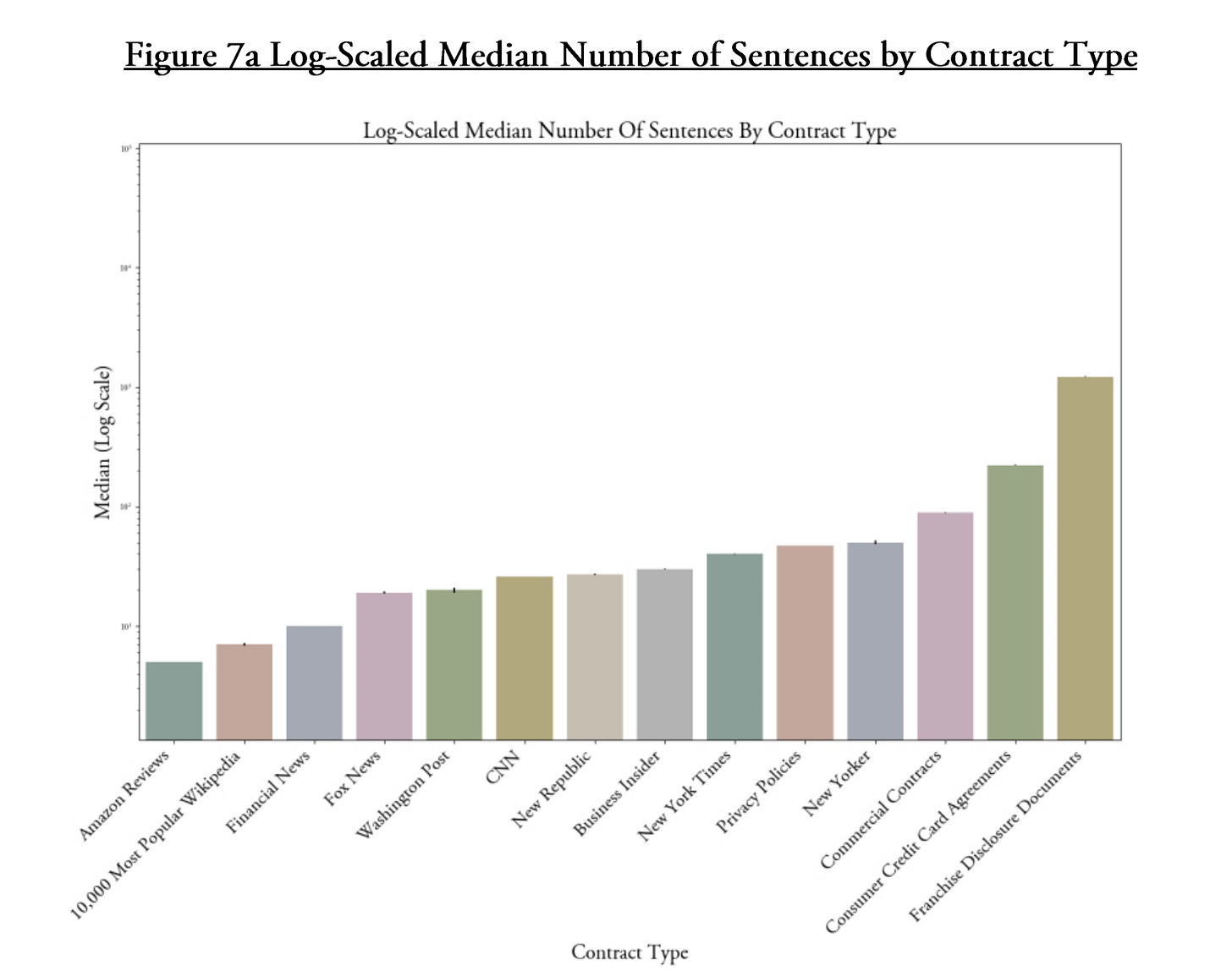

What this shows is that consumer contracts are about as readable on average as magazine articles and online news sources. They aren’t, in other words, particularly dense. But they contain alot of text.

These trends are borne out in time-series data. Consumer contracts and privacy policies are either becoming more readable and concise or holding steady, while commercial contracts are growing more complex and verbose.

I like this paper because it’s counterintuitve without being particularly prescriptive. For around a hundred years, contract scholars and policymakers have bemoaned the fine print in consumer agreements. And, arguably, the rise of those form contracts has fundamentally reshaped our ability to litigate our rights to our collective detriment.

But once you read the paper, you should be way more skeptical of claims that contracts being hard to read is why we’re in the pickle we’re in. Or even that readability is a cognizable political goal at all. If consumer contracts are a social ill, it’s not because they are particularly challenging texts.

Paper #2: Arbitration Clauses Are a Hot Mess

David Horton, Forced Arbitration in the Fortune 500, Minnesota Law Review (forthcoming 2025)

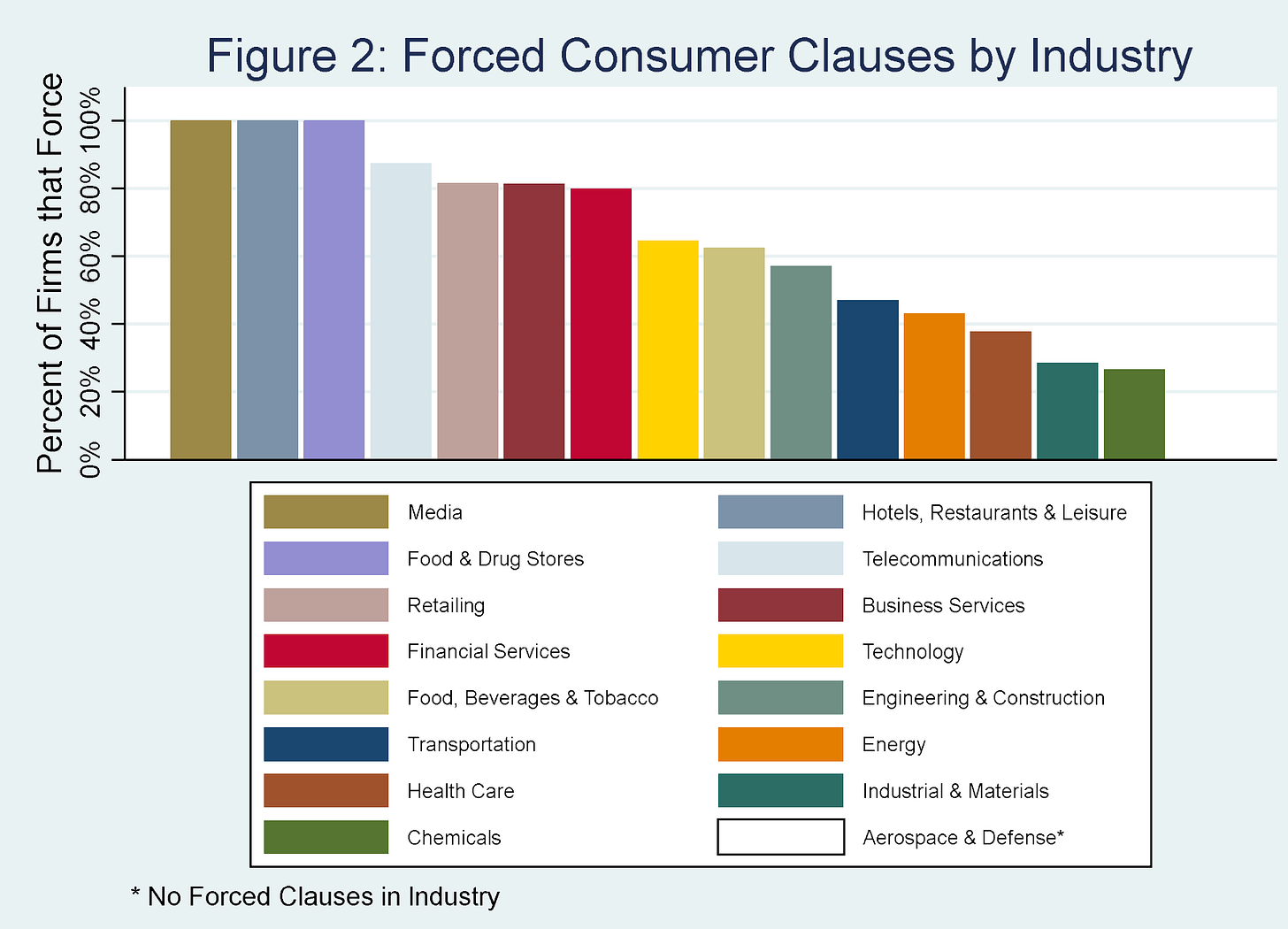

David Horton, of UC Davis, is one of the country’s leading experts on the law of arbitration and its relationship to consumers. In this draft paper, he tries to fill what he (accurately) describes as a gap in what we know about arbitration clauses in consumer-facing contracts of the Fortune 500 firms. Looking at a dataset that combined docket-derived consumer contracts, public terms of use, and other online sources, Horton identified 582 distinct contracts requiring arbitration in disputes with consumers and workers. His bottom line, in line with previous work, is that most firms end up resorting to arbitration in their B2C disputes.

This isn’t the part of the paper that updated my priors, though it’s a good example of the value of descriptive empirical research.

Rather, the paper’s surprising finding is that many of these clauses are simply terribly drafted, with typos that reduced their value to the drafting firm itself. Firms refer to arbitration a notice but don’t draft the actual term, they’ll say someone has to pay fees but forget to identify who, they’ll fail to effectively contract around mass arbitration, and they’ll insert choice of law clauses that affirmatively make things worse for the drafter.

For Horton, this sloppiness results from the complexity of arbitration law: “even firms that are willing to sink resources into keeping up may not be able to do so. These businesses have the worst of both worlds: they incur transaction costs and end up with the functional equiva lent of a ticking time bomb.” Thus, he says, maybe firms would all-else-equal prefer not to have to engage in this arms race.

I’m skeptical of that interpretation, though it’s plausible. Horton is right that consumer arbitration law is become more sludge-like, as common law courts try to escape the Supreme Court’s FAA jurisprudence. It’s not crazy to think that the current equilibrium isn’t helping them and they’d prefer a fresh start.2

A slightly different perspective would be this: many contract terms end up in consumer-facing without a ton of planning, and often are simply copied from other sources. Consumer contracts matter, to be sure, but economizing on transaction costs is routine, and at least some of the time the firms’ brains may not know what their hands are copying or why.

So, what if the slop we see in consumer contracts isn’t the product of a nefarious scheme but rather the accretion of mindless copying? To be clear, firms are absolutely still trying to reduce claims. But they aren’t always good at doing so. The paper thus fits well with an emerging body of literature that contracts as a whole are drafted in really wonky ways, are full of errors and don’t always maximize their drafters’ ends.

Paper #3: Firms Don’t Actually Care About Noncompetes

Takuya Hiraiwa,Michael Lipsitz, and Evan Starr, Do Firms Value Court Enforceability of Noncompete Agreements? A Revealed Preference Approach, Rev. Econ. Stat. 1 (2004)

If Horton’s paper suggests that not all bad terms are highly-evolved apex predators, Hiraiwa and co-authors underline the point. The authors focus on a quirk in a Washington Law that prohibited noncompetes, but only for workers making less than $100,000 a year. Their research strategy was intuitive. They hypothesized that if employers cared about noncompetes even on the margin, what they’d do is slightly bump employees making less than the threshold after its passage so that they could retain the right to enforce a noncompete. That would result in bunching — a few more employees than you’d expect making more than $100,000, and a few less than you’d expect making less, compared to the “smooth” world that existed before the law’s passage.

And they found…basically nothing (apart from general anchor around $100,000 to give employees a “round number” salary). Since this is a non-finding, the authors have to be careful in how strongly they press on it, and they try a variety of different robustness checks. The paper was ultimately published in a peer reviewed journal, so I think the right inference is that their work was competently executed. But the finding is pretty counterintuitive: if noncompetes are such a big deal, why wouldn’t firms slightly perturb their salary arrangements to take advantage of an opportunity to arbitrage around the law?

To learn more, the authors surveyed members of the Washington State Bar Association. They found that some attorneys did advise clients to bump salaries to avoid the law, but relatively few thought it worthwhile to do so. Why? Because the firms never really expected the noncompetes to matter either because the company didn’t expect to enforce them (62% of respondents), it wasn’t needed (51%) or other tools could protect their business interests (49%).

This raises a puzzle: why are firms inserting noncompetes into contracts when they really don’t plan to use them or care much about them? One possibility is that the lawyers (and their clients) think that they can chill worker behavior without enforceable terms though some kind of in terrorem effect. There’s some evidence in the literature for this, though given the low costs of moving from one bin to another it’s not completely satisfying.

A different possibility—suggested by Horton’s paper, and several of mine—is that the spread of noncompetes is as much a story of lawyers churning contracts and justifying their bills as it is deliberate and intentional client choices to lock down labor markets. That is: lawyers have incentives to convince their clients to make changes to their contracts, even when those new terms might not be particularly valuable.

The Big Picture: B2C Contracts Are Sloppy and Not Always Sinister

This cashes out to a more general point.

Consumer and employee advocates tend to have a bit of a paradoxical attitude toward markets and how contracts work within them.

On the one hand, they think that firms exist in Hobbesian worlds, where only the savage and most extractive survive. On this view, every term in every consumer- and employee- facing market must be there because it’s survived an evolutionary process designed to weed out all but those that are maximally-one-sided (subject to reputational constraints). There are dozens if not hundreds of papers asserting that the endless contracts we much click through daily result from the omniscient and evil designs of firms who are taking every marginal penny.

On the other hand, advocates tend to discount the idea that contract terms affect price—largely because (as they correctly point out) employees and consumers don’t read their deals. Without readership there can’t be shopping, and without shopping there’s no point in trading price for law. That’s important because if prices (and wages) reflect terms, whether they are a good or a bad deal is a tricky question to answer.

Thus, for advocates, bad boilerplate results from market forces but doesn’t respond to them. It’s a free good waiting to be picked picked by firms.

And maybe that’s right on the margin.

But the papers I’ve talked about here tell us that lots of consumer- and employee-facing contracts are fairly readable (but unread), contain lots of bad terms (but also some that appear to’ve been inserted by accident), and may reflect the all-nails-need-a-hammer mentality of lawyers looking to justify their monthly bill. That would mean that consumer contracts result from agency costs as much as they do principal liability minimization goals. And that, therefore, they are kind of shambolic.

This doesn’t mean that such deals shouldn’t be regulated. Heck, I think that certain categories of consumer deals should be flat out prohibited. But it does suggest that we ought to learn more about B2C contracts’ production, and what that means for public policy.

I am not an unbiased observer of the paper, having given Yonathan comments at several different points in the piece’s conception and execution.

One of my draft essays—coming soon to your inbox—points out that the evidence that arbitration helps firms’ bottom line is incredibly weak.